TBC..

Finding “The One”.

*Photo taken by Sabina Sarin

Like most people, you saw the words “The One”, and your mind immediately leaped to romantic notions of finding your soulmate and living “happily ever after” ... Well, the “The One” that I’m referring to is not a romantic partner, but the therapist that might help you one.

Finding the “right” therapist is not easy, and ironically involves a process a bit like finding your life partner. In all likelihood, you wouldn’t marry the first person you met or developed a crush on, nor should you expect to mesh perfectly with the first therapist you meet.

Therapists, like all people, come in all shapes and sizes, have their own biases and feelings, strengths and weaknesses, skills and limitations, and one person’s “fire them” might be another person’s “hire them”.

My intention in this piece is to provide you with some tips to help you navigate the process of dating and ultimately choosing the therapist you want to settle down with. Keep in mind here that while some people might only need to date one or two before they find “their one”, others may need to “play the field” awhile longer before they find someone they feel good with, and that can meet their needs. There is no “one size fits all” ; we all have something different to offer. in recognition of this, one might even choose to be “polytherapized”- hiring and working with more than one therapist, each of which has different skills and approaches and caters to different needs or problem sets.... This isn’t a bad idea, as long as it’s been done ethically, and all therapists are aware of each other’s approach, so they can work together instead of against one another!

With that said, imagine you’re looking for a life partner. What’s the first criterion you would look for? If you’re like most people, you may have (sheepishly) thought, attraction. I need to be attracted to them…

Well, you may be surprised to hear that it’s no different here. However, the form of attraction I’m talking about is not physical or sexual. In fact, if you are physically attracted to your therapist (which is actually a fairly common occurrence!), this will add a whole other dimension you might want to explore and work through in your sessions.

What I’m talking about is what draws you to them in the first place? Is it the way they describe themselves, or have been described? Is it their approach? Is it their voice or mannerisms? Were they recommended to you? If so, why? What is the pull or nature of your attraction to them?

Next, what are you looking for in a therapist? Now this might be a hard question to answer. You might not know, or you may even be relying on faulty or insufficient criteria.

Let’s start with some of the more seemingly superficial features. Are you looking to work with someone of the same sex or the opposite sex? This may not matter to you, in which case, you can cast a wider net. On the other hand, you may feel more comfortable speaking with someone of a particular sex, and you should honour that. While for the most part, I would suggest doing what makes you feel more at ease, there is one exception to this: let’s say you are struggling with anxiety in interacting with the opposite sex – in this case, you may want to expose yourself to the feature that makes you anxious in order to work through it within the confines of a safe, boundaried and regulated relationship.

To elaborate on this a little more, assuming you have trouble speaking with women… what better way to help yourself overcome this difficulty than to speak with a female therapist? You will simultaneously be confronting the physical stimulus that makes you feel a little uncomfortable, while also having the opportunity to address your concerns with someone with lived experience with the quality that makes you uncomfortable. Discomfort is the pathway to growth.

The next aspect you may want to consider is the race/ ethnicity/ cultural background of the therapist you choose to work with. Again, you may feel that this feature doesn’t matter for you, in which case, move to the next step.

However, if you are someone that is struggling with issues related to culture/ ethnicity, this may matter a LOT and you may want to find someone of the same background who will better understand your concerns (without guilt/ defensiveness/ overeagerness/ fragility). For example, if you are a native French speaker, you may want to find a francophone therapist for ease of communication and for a sense of comfort in knowing that certain nuances in humour or self-expression may be understood. Alternatively, you may be BIPOC, and wanting to address past racialized experiences and the ways in which they might hobble you in the present. Perhaps you are navigating the difficulties that come with being raised within and influenced by a cultural tradition that is not mirrored by those around you. In these cases, working with someone with an appreciation of the ways in which these embodied experiences can influence daily living may be a necessity. You do not want to have to “school” your therapist or “defend yourself”, nor should you have to sidestep, reduce yourself, tread gently or otherwise cater to your therapist’s fragility, guilt, or discomfort (which may be masked as overzealous attempts to prove themselves to be “colour blind” or otherwise non prejudice). And let’s be honest, the goal is not to become “colour blind” (what’s wrong with seeing colour?) - its in doing our work enough so that we can see a colour and celebrate it, without associating it with meaning and stories and judgement. While some of your therapists’ sensitivities or “racial privilege” might be worth addressing in session, it also should not form the focus of work in this area. It can be hard enough to have these discussions without having to worry about the impact it will have on your therapist, or without worrying about making yourself more “palatable”. That said, while cultural similarity can be helpful, it also does not mean that someone of the same background will necessarily share your feelings/ experiences or that someone a different background will not understand, appreciate or be open to the kinds of racialized/ cultural discussions you need to have. Do your research and find out… If your therapist is not open to, or is harsh or anxious about having these kinds of discussions, move on.

The next factor is also tricky: Sexual Orientation. You may not want to inquire about your therapist’s sexual orientation directly, though some therapists that are on the LGBTQIA2S+ spectrum, or allies to people on it, may self advertise that way.

If you are struggling with anxieties about “coming out” or have had oppressive or discriminatory experiences as a result of your sexual orientation, you may feel more comfortable working with someone that is also on the spectrum, or who specializes in working with LGBTQIA2S+ issues. This is not a concern to minimize. If you meet with a therapist, and your sexual orientation is something that suddenly feels like the “elephant in the room” (and you know it’s not coming from you), or you find yourself becoming defensive, you may want to inquire about your therapist’s experience, skill, or comfort level in working with LGBTQIA2S+. If they are unable to answer this, or become “touchy”, you have your answer. If however, this is a part of your identity that you have already come to embrace, and your therapist’s orientation and expertise in this area is irrelevant to you, then you can check this off your therapist “wishlist”.

Finally, with respect to demographic or identity factors, there’s age. While you most certainly don’t want to come right out and ask your therapist how old they are, their physical appearance, and most importantly, their years of experience are going to give you some indication of this.

Now why would their chronological age matter? Well, imagine you’re going into the hospital for a treatment – would you prefer to work with a trainee or someone that has decades of experience performing the treatment of question? Contrary to what you knee jerk reaction might be, this is actually not a simple answer.

Trainees tend to be “fresher”, more “up to date” with knowledge in the field and they often feel they have “more to prove” so they work harder. They may however also display more ego fragility and defensiveness as a result of these same features, and you certainly cannot underestimate the skill and wisdom that comes with years of experience working at something... If you choose to work with someone that is young and early in their career (less than 5 years), you may want to ensure that they have their own clinical supervisor, whose wisdom and experience you can also benefit from.

On the other hand, “seasoned experts” in the field, while often a “blessing” to work with, also get “lazy”. They’ve typically been seeing the same types of clients for so long they no longer feel challenged. They tend to think “they’ve seen it all”, so they start working with one eye (or ear) closed, their minds already predicting what you’ll say, a diagnosis formed within 5 minutes of meeting you. These kinds of experts might also be more defensive to being questioned or challenged. In which case, run! This is not the basis for a safe therapeutic relationship.

In addition to therapist age, your own age may also come into play here: if you are a teenager coping with some of the really hard changes that occur in the body and mind during this time in your life, you may want to see someone that is younger, more “connected” to “youth” culture, and with experience working with adolescents; someone that will likely empathize with your struggles without being minimizing or patronizing. On the flip side, if you are moving into the retirement stage of your life, struggling with “empty nest” syndrome or otherwise dealing with the challenges that come with aging, you may find yourself better held by someone who has been down “that road”, or at least closer to it, than someone fresh out of school.

But regardless of age, do ensure that whoever you choose to work with is licensed with the regulating body in their province (e.g., the College of Psychologists in Ontario), and has a minimum of a Master’s degree in their area of expertise. If you do choose to work with someone with a Master’s level of training, remember that it is only people with a PhD, or MD, that are licensed to make psychological diagnoses and that is only after having done a thorough psychological assessment (a few questionnaires are not enough!). Anyone that jumps to diagnosing you without proper training, licensing, or a thorough assessment should set off warning bells. Also, note that some insurance companies will only cover payments for therapeutic work with doctoral level psychologists, which may be an important factor to consider for many.

So that’s the “surface” level stuff… Sort of like the “preliminaries” on a dating app., like Bumble. But now let’s get into the proverbial meat and potatoes, the “stuff” that is actually within your therapist’s “control”.

The therapeutic relationship is a sacred one and should be treated as such… by you, and by your therapist. Therapy is not a business - its a service - and it is ripe with pitfalls, vulnerability, error and repair. It is an opportunity to delve deeper into your psyche and into uncomfortable territory to make quantum changes in your body/mind, to learn to create and sustain the kinds of human relationships you desire, and the list goes on. Which means that this territory needs to feel safe, but too safe. In therapy sessions, we need to be mildly activated (triggered) in order to be able to have corrective experiences, and in order for change to happen. So if you are coasting through your sessions, leaving feeling great and never really feeling the ripples, it isn’t therapy, its a supportive space, and meaningful change cannot occur. But you don’t want to be consistently dreading your sessions either – feeling as though you’re entering shark ridden waters and leaving with chunks taken out of you. The space needs to feel “safe enough” to do the work of leaving the shallow end to swim a bit, before returning to even ground.

But what actually makes a space safe? This is an important question. Please don’t feel you need to believe anyone that tells you “this is a safe space”, especially from the onset. An appropriate response to this might be, “Really? In what ways?” A space certainly isn’t safe simply because someone says it is. And simply because it’s safe for your therapist (or another client) doesn’t mean that it’s going to feel safe for you. Safe spaces are co-created; they don’t just exist as preset features. You don’t enter a safe space, you build and shape a safe space. And one of the most important aspects of being able to do this, is trust.

Trust is a little like safety. I don’t expect my clients to trust me right off the bat. Why would you? You don’t know me, I don’t know you. In fact, it’s a little foolish to trust someone (fully) just because they’re in the role of therapist. And anyone that tells you that you need to trust them, I would want to know why? What is it about them that should engender trust? You don’t need to trust someone just because they tell you to. In fact, the people you can trust probably never need to convince you to. Trust is earned, shaped, corrected, strengthened. It is built on a bed of honesty, reliability, consistency, credibility. So if you’re seeing an expert in a particular field, you might have more trust going into the relationship than if you were seeing someone with a sprinkling of knowledge. But even then, that degree is no guarantee. You may trust an expert to provide sound knowledge, to know the techniques, but do you trust them enough to be vulnerable, to demonstrate your insecurities, to delve into the hard and sometimes “yucky” stuff? Do you trust them to stay boundaried, to put their egos and self interest away (as much as is humanly possible), to see you/ hear you/ believe you, and to steer you accordingly? Do you trust them enough to let go and dive every once in awhile? It’s important to have a therapist that you can question, and talk to about the “uncomfortable stuff” and while you’re doing so, you are justified in wanting to feel safely held and accepted, not secluded and judged.

You may feel like you’ll never trust someone to this extent, and you know what? That’s also okay. In fact, some might say you should never trust someone 100% . Trust is not an “all or nothing” experience. Some level of reservation and critical thought is always required. You may be glad to know that the mere fact that you have even decided to see a therapist, perhaps already booked an appointment and had your first session signals the presence of a base level of trust. Trust is demonstrated simply in choosing to enter a therapist’s office and in disclosing some of the more intimate details of your life. There is trust in entering a nonreciprocal relationship that involves a power structure. And the more trust there is in the therapeutic relationship, the more effective the therapy will likely be. But again, that that trust will be built and shaped over time. Rather than “I need you to trust me”, look for a therapist that says “what would help you trust me, or what makes it hard to trust?” “what is about this relationship/ space that feels scary?” “what do you need more/ less of in order to trust me? And if you choose to address this lack of trust with them, notice whether your hesitations are held and explored, or if you walk away feeling guilty and doubtful.

Presuming you have found someone that earns this base level of trust, what would augment it? Someone once told me, “if you ask your therapist, what do you not do well? What are your shortcomings as a therapist?” and they can’t or won’t answer that question, RUN. Therapists are humans, and as mentioned earlier, we all have our limitations, biases, shortcomings, and weaknesses. And you have a right to know what these are (and to ensure these aren’t being projected or enacted with you!).

You also may want to know what your therapist does really well - their strengths, skills, approach, and the kind of clients they excel with (as no one works well with everyone and everything). Can you live with your therapist’s shortcomings and are you drawn to their strengths? (Ironically, this is also a question you might ask yourself when finding a life partner!) If you choose to give your therapist feedback in your sessions about what you like, or just as importantly, what you don’t like, how do they respond? Do they take it in, and explore it with you? Are they gracious, curious and responsive.... or do you suddenly feel as if you’ve done something wrong? Or even worse, do they become defensive, turn your comments around and make it about you? (Some of which might be, of course, but certainly not all of it). If they do become defensive (it happens to all of us at times), do they later own it, and engage in repair with you? There are many therapists that have been trained in a traditional school of thought that is “expert-centered”, and they consequently neglect to see their own role (e.g., flaws, biases, mannerisms, relational dynamics etc) in the therapeutic outcome. They may be more inclined to see everything as a reflection of “you”, your interpretations and your biases… While there is certainly validity to this line of thinking, therapy is a relationship, and you want to see someone that is going to acknowledge their part in the relationship, and that includes making mistakes. Therapists may have expertise, but they are not experts on you. You are your own best expert and you need a therapist that can help you tap into that wisdom and self knowledge.

On the other hand, some therapists take the “personal” element a little too far, and stretch the boundaries of what is actually a non reciprocal relationship into one that feels a little “too intimate”. If your therapist thinks about you a lot out of session, discloses frequently about their own life and leaves you feeling as if you need to take care of their feelings, plant a red flag. While it is important to be kind to your therapist, and to recognize when you are projecting onto them, you are not there to take care of them. And if you feel you need to, that is a pattern worthy of exploration (is it your pattern, or theirs?). If you find yourself wondering about your therapist, and asking them personal questions about their life, (which is normal to some extent) why is it important for you to know this information? If your therapist answers these questions without hesitation or curiousity, how does that feel for you? Disclosure on your therapist’s part is okay, but it should ideally be meeting a therapeutic need of yours. If your therapist shares something that makes you feel uncomfortable (and you’re left thinking, “oh I really don’t know if I wanted to know that”) tell them. You should not feel left carrying the burden of their disclosures..

In session, your therapist may be “friendly” or “caring” with you, but they are not your friend or primary caregiver; you can “depend” on them (to provide the established and agreed upon features of a safe therapeutic relationship), but without developing dependency on them... Therapists have their own personal opinions, belief systems, and practices (e.g., religious beliefs) but these should be owned, and not imposed upon you. I once had a body worker that during a session, spoke to me about my past lives… When I told him I wasn’t sure if I believed in past lives, he became quite upset and defensive. A pattern developed of him projecting beliefs, stories and opinions onto me, without sufficient explanation, and often to the neglect of my own wisdom and wishes. Expressed upset or disagreement on my part was met with the critique that my interpretation that was the problem, rather than his boundary violation. Needless to say, this therapeutic relationship didn’t work out…

What we’re talking about here, is boundaries. Boundaries come in three forms – physical (distance / space), emotional (disclosure), and spiritual/ psychic (energetic). In any relationship, but particularly a therapeutic one, boundaries are necessary, not optional; it is for you and your therapist to navigate these murky waters together to establish ones that feel safe for both of you.

So far we have been talking about what are known as non-specific factors, factors that highly influence the therapeutic process and its effectiveness, but are not specific to the therapeutic modality itself. But this guide wouldn’t be complete without addressing the factor most people think is most important, and that insurance companies can be sticklers about: the therapeutic approach.

If you’re like most people, you’ve heard certain the name of various therapy approaches thrown around - they often follow bandwagons or zeitgeists. Once upon a time, CBT or cognitive behavioural therapy was “all the rage” - at a later point “mindfulness or MBSR” - and now “somatic therapy”. Most of the time these bandwagons have little to do with the effectiveness of a therapy itself. There is no hierarchy with some therapies being intrinsically better than others. There are numerous approaches out there that are excellent and highly effective. What is most important in choosing a therapist is that they use a form of therapy that has been empirically (scientifically) tested and supported for the problem you’re struggling with, keeping in mind that some of the most influential parts of a therapy can’t always be operationalized or tested (e.g., therapist warmth or positive regard). Moreover, some therapies (e.g., CBT) are more amenable to scientific testing because they are easily manualized and thus, replicated; these therapies are usually the ones that are most suitable for very simple and uncomplicated issues (e.g., simple phobias)… This is generally why insurance companies like them - they’re short term, uncomplicated, and “well tested”... except for where they’re not (e.g., complex trauma)! In general, the more complex the case or issue, the less likely it is to be effectively treated by a readily manualized treatment.

So the work here for you is in knowing what approach works for what you’re struggling with. CBT is excellent for uncomplicated depression and some forms of anxiety. EMDR is highly effective for single episodic PTSD (e.g., car accidents), but much less less effective for complex PTSD and developmental traumas (which are more chronic and less “event based”). In the case of the latter, EMDR should not even be used until a significant amount of time has been spent building rapport and trust, and developing one’s repertoire of positive coping resources. Mindfulness-based therapies are wonderful for working with anxiety and general wellbeing, but should not be used for people with psychosis, or high levels of limbic system instability. Finally, some therapies are more effective for certain people at certain times (e.g., some respond better to somatic approaches like sensorimotor psychotherapy, while others respond better to more emotion focused methods such as DBT). And of course, there are adjunctive therapies such as yoga, that have been scientifically tested and established as effective as treatment for a number of illnesses, though it typically should not be used as a stand-alone treatment. In addition, where certain forms of yoga are effective for some problems, they may be less effective for other illnesses. For example, while hatha and restorative yoga are excellent for generalized anxiety, they may not be particularly helpful for depression, for which a more activating, vinyasa-style practice is indicated.

You may be wisely asking yourself at this point “How am I supposed to know what therapy works best for what?” A quick online search can usually point you in the right direction for the best approaches to treat your concern, with the caveat that the credibility of the online source is important. Much of what is “out there” is politicized and often sponsored, and so sticking to medical and scholarly sources is advised.

Now, presuming you have found someone who specializes in the type of approach that has been found to be effective for your problem area, your next concern might be how well the practitioner actually applies their tool. Therapy is an art and a science; you can give every therapist the same type of paint but some artists simply work better with oils than others do. In fact, one of the single strongest predictors of the effectiveness of a therapy (outside of its own merit and suitability) is how much the practitioner “believes in it”, which will usually determine how well they apply it.

The next factor determining a therapy’s effectiveness is how well you take to that approach. Even an exceptional artist may not paint equally well on all canvases (e.g., some work better with large canvases, others with small). In other words, a highly skilled CBT practitioner may find this method less effective with a highly intellectualized and rational client, as their client may already be prone to using “rationalization” as a defence or coping strategy (thereby bypassing the experiential). So while you may like the kinds of paintings the therapist creates, and they may feel like “your style”, it may simply not suit your gallery. As the old adage goes, sometimes what we want isn’t always what we need.

Finally- and this pertains specifically to the area of trauma therapy, or to those of you looking for someone to work through past traumas with - trauma is not like a lot of other psychological issues. Unlike other mental health issues, trauma is stored in the body, not the mind. This means that in order to work with your trauma, you need a therapist that is trained in somatics (body therapies), especially when working with early stage or unresolved trauma. Trauma therapy involves its own distinct toolbox of skills and subscribes to unique principles such as clarity, transparency, non hierarchy, empowerment, choice and control. Unlike other talk therapies, it works “bottom up”, not “top down”, where talking about the content of trauma is secondary to working with the bodily effects of the trauma. So if your therapist allows you, from the onset, to launch into the details of your story (as people are often eager to do), to emote without exploration of the facets of your emotion, and analyzes or rationalizes your thoughts about the events, WITHOUT exploring what is happening in your body (including your tone of voice and mannerisms), then you are not in the right hands.

When it comes to trauma informed sessions, you should feel like you have “choice” and the ability to say “no” to any intervention your therapist suggests. Your therapist should be transparent about what they are doing and why, leaving room for collaboration and boundary setting. And while it may sound strange, it may also be important that you like the sound and cadence of their voice. In no other area is vocal prosody so important (vocal tone, speed, pauses, timbre, frequency). Your therapist’s voice and demeanor should help you stay regulated and calm, so if they themselves sound like they are running to the finish line, ask them to slow down. And they should be doing the same with you, if for no other reason than to promote the regulation of your nervous system. It is important to gather information but it should be done in a way that is calm and well paced.

Some final questions you may want to ask yourself to help you decide whether a therapist feels like the right fit for you:

1) Do I feel seen? Heard? Believed? Understood?

2) Do I feel like my therapist is really present and engaged/ invested? Or do they seem distracted, divested, and/or unable to remember the things we speak about?

3) Do I feel like my needs are being attuned to? If not, when I signal this, does my therapist respond in a way that feels good? Sometimes misattunement is necessary, but repair and transparency is paramount.

4) Do I feel like my therapist is talking at me, or to me? Does it feel mechanistic or humanistic? In other words, do I feel like I am being treated as “a textbook case” or do I feel like I am being seen as a unique human being, and authentically engaged with as such?

Now chances are, you are not going to find someone that meets ALL of these criteria, but you also don’t want to “settle”. That said, even a therapist that meets many of these criteria will fall short sometimes (we all have “off days”) but they should be able to engage in a process of repair with you. As a general rule, you should feel good in your therapist’s presence, despite what you might be carrying and despite the distress/ turmoil that comes with exploring it in session. Therapy is not supposed to be “easy” or “comfortable” and the amount that you get out of it will depend on the work you put into it, not on how “well your therapist does”. Your therapist is your guide, not your mechanic, and they are there to make navigating the unknown a little more tolerable. They are there to help you find your answers, not supply you with theirs (education aside).

At the end of the day, the person you really need to trust on all of this is yourself. Deep down, you know what you need and your instincts and intuitions are invaluable. This includes the instinct on whether a particular therapist feels like a good therapist for you…. Or at least a good enough therapist for “right now”.

Best of Luck!

What's Trauma Got To Do With It?

“YES, I EXPERIENCED [ BAD EVENT ] BUT IT WASN’T TRAUMA; I MEAN, IT WASN’T THAT BAD. OR AT LEAST, I WASN’T TRAUMATIZED… I JUST PUT IT BEHIND ME, DIDN’T THINK ABOUT IT, AND MOVED ON...”

*Photo taken by Sabina Sarin following a volcanic eruption and hurricane in Guatemala.

“I’M NOT TRAUMATIZED, I’M JUST [ANXIOUS/DEPRESSED/STRESSED/ ETC.]”

I cannot recall the number of times I have heard these sorts of statements from people that actually have quite significant, unresolved traumas... While no one wants to minimize a severe trauma (e.g. genocide) by placing it in the same category as a smaller scale stressor (e.g., a narcissistically abusive relationship), what I often see happening is that these smaller traumas go unacknowledged, and thus untreated. As a result, they often lead to instability in the nervous system (what we commonly think of as being “triggered”), manifest as physical or mental illness, or lead to future traumas. Typically, these manifestations are coping strategies, reaction patterns, or defences that mask the initial trauma or mitigate against feeling its effects. The untreated trauma not only puts the individual at risk for future illness, but also effects future generations. Trauma often gets passed forth within families and systems for many generations, leading to what is known as intergenerational or intesectional trauma. The purpose of this piece is to clarify some myths around trauma and to provide some of the trauma fundamentals that most people in this complex, and often chaotic, day and age should know.

What is trauma?

I think when most people think about trauma, they imagine the unimaginable: life or death situations that are terrifying and inescapable– war, genocide, torture, natural disasters, viral epidemics, bad accidents, etc. - what we call, “Big T Traumas”.

*Photo taken by Sabina Sarin in Poland

*Photo taken by Sabina Sarin

These kinds of trauma survivors typically go on to develop what we refer to as “PTSD” (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder), which involves frequent memories, nightmares and flashbacks of the event, avoidance of reminders of the event, emotional numbing/ detachment/ isolation, and chronic symptoms of physical arousal (increased heart rate, constriction, an exaggerated startle response, irritability or anger) (APA, 2013).

However, this is a somewhat incomplete definition of trauma and does not capture the range of experiences that can lead to a traumatic response. Nor does it represent the prevalence rates that we see for causes of PTSD, or the locus of the burden on the health care system. In actual fact, trauma is less about the event, and more about how one experiences the event. In other words, more crucial than whether one’s life is actually in danger is whether one BELIEVES that they are in danger and how much control (and support) they believe they have in coping with that danger. In other words, an event that results in someone feeling fundamentally unsafe, terrified, helpless and alone, has all of the ingredients for trauma. This can include anything from being followed at night on a deserted street, to being in an abusive relationship or growing up in a volatile (unsafe) or unstable home environment – what are known as “Little T traumas” . These events are not directly or intrinsically life threatening but may shatter a sense of safety or security, trigger other past traumas or wounds, produce traumatic charge in the body, and ultimately result in similar effects to other “Big T” traumas. According to the Center for Trauma and Embodiment, “trauma is something that is done to, forced upon, or taken away from someone, without their consent (or ability to consent) and beyond their control. “

At the same time, it should be noted that many people who experience life threatening situations (e.g., combat soldiers) often do not experience them directly as traumatic, and do not go onto develop PTSD. In fact, somewhat ironically, war veterans have some of the lowest rates of PTSD (Spence et al., 2011) amongst all groups of trauma survivors, perhaps due to the many protective factors inherent in their environment, including their greater levels of empowerment (choice/ control) and their built-in support system or “brotherhood”). In contrast, groups of trauma survivors that are more marginalized (e.g., LGBTQIA2S+, BIPOC, people with disabilities) are often over-/dis(em)powered, are typically alone in the experience of their trauma, and often more highly stigmatized and thus, less supported; consequently, they tend to be at greater risk for traumatic effects. And so given this, perhaps it is not so surprising that of all groups of trauma survivors, the highest rates of PTSD are found amongst victims of rape and child abuse (Spence et al., 2011). Right now, child abuse is considered to be the primary public health issue in both Canada and the US due to its pervasive impact on all aspects of mental/ physical health, and its cost on the health care system trumps almost any other illness (including cancer and heart disease) (van der Kolk, 2014).

Photo taken by Sabina Sarin in Vietnam

In fact, child abuse, or early attachment trauma (which includes fetal injury) is the single strongest predictor of whether someone will develop PTSD following an extreme stressor. Attachment trauma involves chronic experiences of feeling unsafe, hurt and helpless within an important caregiving relationship... (i.e., those that are supposed to love and take care of them). These children typically experience their homes as involving high levels of adversity, stress, chaos and/or low levels of support. They often develop what is known as Developmental Trauma, or Complex Trauma (CPTSD). On the other hand, children that grow up with a sense of safety, security, and nurturance with their caregivers tend to be more resilient following a potential life or death situation, and are more likely to bounce back afterwards. To eradicate child abuse would be to cut prevalence rates of depression by half, alcoholism by two thirds, and suicide/ homicide/ domestic violence by three quarters (van der Kolk, 2014).

In addition to developmental traumas, institutional or “systemic traumas” represent another form of trauma in which one is harmed by the very structure they rely or depend on to keep them safe (e.g., the police force, army, criminal justice system, or health care system.) These kinds of traumas are, unfortunately, highly common, and include things like racism, homophobia, patriarchy, poverty and discrimination on the basis of mental or physical disabilities. These forms of aggression or boundary violations (oppression by those with more power) exert their effect through invasion of the body/ mind/ spirit, and signal to the recipient that they are not being considered to have the same equality, integrity or dignity as someone else outside their “group”.

*Photo taken by Sabina Sarin in Guatemala

But also, people with these kinds of complex trauma normally go on to develop a number of other mental and physical illnesses including depression, anxiety, (auto)immune disorders, eating disorders, personality disorders, sexual disorders, autism and neurodiversity, as well as substance abuse disorders (often as defences against, or manifestations of the underlying trauma). This is why being carefully and thoroughly assessed by a trauma-informed psychologist (who have a specific toolbox of skills), and discussing the impact of some of these early childhood experiences can be really important. The effects of these kinds of experiences do not just “go away” by “moving on” or “rationalizing/ contextualizing” or “pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps.” Rather, they can lay dormant or masked for years and then show up as full blown illness. Conversely, very often, treating the underlying trauma is enough to eradicate the other symptoms (e.g., depression or substance abuse) altogether.

So you may be wondering at this point, why are the effects of trauma so devastating and far reaching?

What actually happens to the mind and body when there is a trauma?

I say the mind AND body, because despite popular thinking, trauma is not a mental disorder, its a physical one. Trauma is stored in the body, not the mind. Experiencing trauma changes the way the brain and nervous system develop in structure, or are wired (a form of neurodiversity), and so it logically affects every aspect of our lives (including our beliefs, feelings, and choices).

When faced with danger, our nervous system, and particularly the sympathetic nervous system (which includes the brain, spinal cord and various organs) becomes active, and hormones (such as cortisol) are released to help us take action, whether to fight, flee, freeze, or fawn. When we’re safe, the SNS deactivates, adrenaline (charge) is released, and the parasympathetic system (PNS) takes over so we can relax, regulate and integrate (rest & digest). In other words, on a more primitive level, we see the bear, we get scared, we run... when we know we’re safe, we shake it off, and relax.

What happens when there’s trauma is that the nervous system becomes overwhelmed by the event that it is trying to process and tolerate (because one feels/is unable to take the necessary action to combat the size of the stressor), so it gets stuck and the shift from SNS to PNS isn’t completed. As a result, the leftover electrical charge (from being in fight/ flight/ freeze mode) gets stored in the nervous system and often shows up in the form of various symptoms, such as emotion dysregulation. In other words, this stored stress response causes shifts from hypervigilance (alertness/ panic) to hypoarousal (collapse/ depression), and vice versa, which if untreated, start to affect every aspect of our lives (the byproduct of living under chronic stress).

Another way to look at this is that during a traumatic event, or when triggered, a split occurs between the rational mind and the rest of the mind/body – the rational mind shuts down or goes “offline” (and so we are no longer able to be relaxed, controlled, clear thinking, and grounded) and we consequently act from the more emotional, primal, parts of the brain (whose sole mission is to keep us alive).

But to understand this, you need to know a little about the brain.

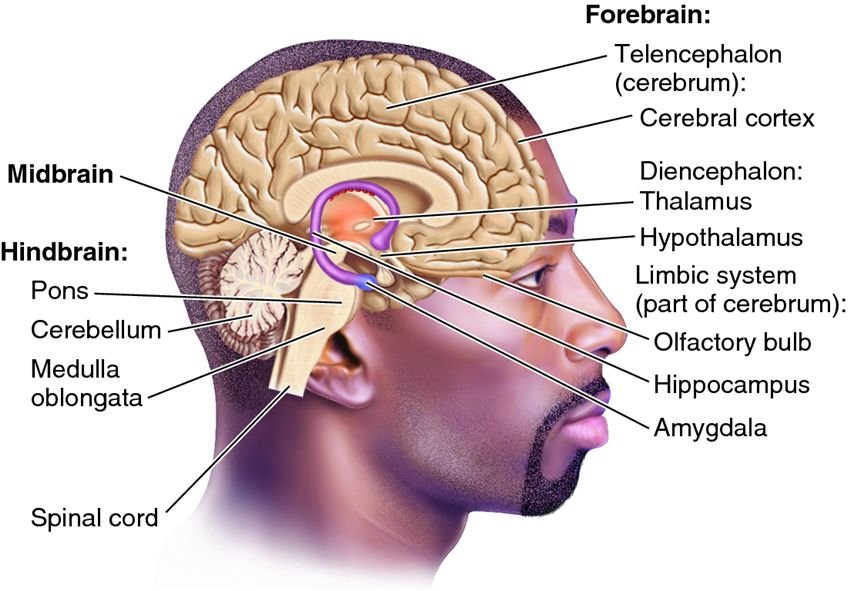

There are three main parts to what is called the Triune brain (Maclean, 1960):

1) Hindbrain – which is considered the reptilian part of the brain (or, “the lizard” as it is most primitive part and concerned only with survival. It includes the cerebellum, pons, and medulla oblongata.

2) The Midbrain, or Limbic System – which is considered the mammalian part of the brain (or, “the mouse”), which is common to all mammals and concerned with emotional security. It contains the thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, basal ganglia, and amygdala, all of which are strongly impacted by trauma. The emotional centers are highly active, processing impaired and memory fragmented.

3) The Neocortex or Prefrontal Cortex– which is new mammalian brain (or, “the monkey”), concerned with attachment and regulation processes, as well as rational thinking and emotion regulation. In trauma, it is less active and cannot override the activity of the other more emotional parts of the brain (which is why you can’t “think your way through a trauma response”.

But you may be asking yourself, what makes an event too much for the brain to process? Or how come some people get traumatized by an event when another doesn’t?

And this is where individual differences, such as early childhood experiences, come in. Individual differences emerge from everything that came before the event, and this includes past traumas, one’s physical and mental health at the time of the event, one’s capacity to process the event without becoming overwhelmed or stepping out of “ease” (the window of tolerance) , how much social/ community support they have to manage the event and its consequences, and one’s personal belief system regarding choice, capacity, and fear tolerance… all of which will ultimately determine the effects of the event(s) itself.

A closer look at this indicates that much of this concerns the size of your window of tolerance for stress. The window of tolerance is the intensity of stimulation that you can experience while still remaining calm, controlled and grounded. When we are outside our window of tolerance, it means that a situation has become “too much” for us, and we either become defensive (entering the Faux Window of Tolerance) dysregulated/ panicky, or shut down.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, we inherit our window of tolerance from our parents, and from how they responded to us when we were upset (a process called interregulation). Generally speaking, when we were upset, if they helped to soothe us and repair our emotions, we develop a large window of tolerance that allows us to have a sense of safety, trust, good relations with ourselves and others, and a capacity to tolerate and manage our emotions (self soothe).

If, however, our parents reacted in a way that caused us more distress, or that failed to adequately soothe us, then the brain develops differently (particularly the right side of the prefrontal cortex). This often leads to the development of an insecure attachment system, a more narrow window of tolerance, and consequently, more defensive coping (e.g., isolation, substance use).

In general, the wider the window of tolerance, the more intense arousal one can experience without becoming chaotic.

So, if you happen to have a more narrow window of tolerance, and then experience an event that is too much to process and the processing gets interrupted (e.g., you can’t run away, or you can’t fight back), that event is likely to lead to a traumatic response. Thus, one of the main goals of trauma informed therapy is to help clients “resource”, as a way of increasing the size of their window of tolerance, and building resilience.

Why can’t I remember details of my trauma?

It is possible to experience a traumatic event and not remember most of it, particularly if it occurred early in life, during one’s nonverbal stage of development. Sometimes people report just having a “feeling” that something bad happened, but having no actual memory (we hear this a lot with survivors of childhood sexual abuse).

And this is because not only is trauma stored in the body, but it is stored in the part of the brain that is nonverbal, visceral or experiential. And the part of the brain that sends information from the experiential part to the narrative intellectual part isn’t usually well developed in childhood, so traumatic experiences are often registered as “bad or yucky feelings”. In addition, the hippocampus, which is involved in memory formation and storage, is often impaired and/ or of a different structure in trauma survivors, leading to incomplete or fragmented memories.

But whether the mind remembers or not, the body remembers - “it keeps the score” (van der Kolk, 2014). And often all it takes is another experience that triggers a similar sensation in the body, to activate these old experiences, which ultimately allows the memory to resurface.

You may be wondering at this point, if trauma survivors have brains and bodies that are wired and structured differently, is full recovery or healing possible?

And the answer is YES (thank goodness for neuroplasticity!). But we have to go about it a bit differently than most other disorders.

Since trauma is stored in our body we need to heal it through the body.

And so “rational” therapies like CBT or psychoanalysis aren’t particularly effective, at least not at first when emotional management and embodiment is a struggle. You may know of people who talk something to death but it only seems to make it worse, or who have a clear understanding of their issues, but nothing changes. There are times when simply talking about or analyzing the problem “bypasses” the solution.

Instead, early in trauma healing, psychomotor therapies are the way to go, because these navigate around the rational brain and tap into the more primitive part of the brain where trauma is stored.

The idea behind any good trauma treatment is that it combines what is known about the brain and trauma, with the principles of mindfulness, breathing, resourcing, and healthy attachment

A person that is healed is one that feels safe, whole, integrated and accepted… and this happens largely through work that helps to release the built up electrical charge in the nervous system so that ease and gentle movements can start to happen again.

There are 3 stages that a trauma survivor will go through in the process of healing, and it’s important for your therapist to know what stage you’re in, because it tells them what needs to be done (Herman, 1997):

1) chaos – hyperarousal (chaos) to hypoarousal (disconnection)

In this stage, you may feel very dysregulated and fragmented (the word “broken” is used a lot by survivors to describe how they feel). The most important thing at this stage is to find a therapist you trust and feel safe with, that you can form a secure attachment with, that offers you choice and control and that has a strong understanding of trauma and its effects.

On your own, practices such as running, dance, gentle weight lifting, physical labour, restorative yoga, qi gong, and martial arts are wonderful adjuncts to help create some stability and to facilitate a release of built up stress. Paramount to this stage is ensuring that the trauma is over and feels over, which may include getting yourself into a new environment that feels SAFE. Support building (e.g., through support groups) is also essential.

2) containment – safety & stabilization

In this stage, you may feel more safe and it may feel like the traumatic event has actually come to an end. The work in this stage is to develop self soothing strategies, including grounding, emotion regulation, and orienting to the present. This stage is all about helping yourself become more resilient!

With your therapist, you should start to move into mindfulness work, relaxation work and resilience building.

On your own, yoga, mindfulness, dance, meditation and any practice that gives you pleasure (e.g., hiking in nature) is highly recommended.

3) coherence – integration

In this final stage, you may feel stronger, safer and more stable. This means you’re ready to start the process of safely letting go of control. This is the stage in which to revisit the memory of the trauma and its effects (but in diluted and titrated ways), and to complete the survival responses (e.g., fight/ flight/etc.) that once got thwarted. With your therapist, the trauma is processed in a slow and embodied way to facilitate the release of traumatic charge and to promote post traumatic growth and healing. Methods like EMDR, Somatic Experiencing, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, Cognitive Processing Therapy, Neurofeedback, Brainspotting, Internal Family Systems, and Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy can be excellent approaches at this time.

On your own time, its important to keep feeling, keep moving, and keep orienting to what feels “good”, after dipping into what feels “hard”.

Final tips on the healing journey: The DO’s

• Do keep your body moving, even in small ways; let it move how it wants to, even if it “looks” strange

• Do pay attention to your body and your limits, and set your boundaries

• Do read about trauma and express yourself through writing, creating, or by telling your support network how you feel and what you need

• Do orient to the present and the positive, feel your feet on the ground, find your centre, and feel your bodily container

• Do create a support network: support groups, positive environments, positive interactions; do find at least a few people with whom you feel safe and supported – trust your instincts

• Do take control and find ways to take your power back

The DO NOT’s:

• Don’t go too fast with anything – be patient and gentle with yourself

• Don’t spend too much time with the thoughts in your head – most of them likely aren’t true

• Don’t avoid or try to make it go away – but “do” choose “when” and “how much”

• Don’t blame yourself – it’s NOT YOUR FAULT, but healing is your responsibility. Try not to judge yourself …or your symptoms.

• Don’t isolate – but do not spend time with people that make you feel bad about yourself or your symptoms

• Don’t give up - Whatever happens, even in the hardest moments, do anything at all, even if it’s just to take a deep breath, and then another and then another after that... but do not give up. I promise you it will get better.

Healing is possible for anything and anyone.

IF this article has resonated or spoken to you in some way, and you’re interested in learning more, in being trained, or are interested in treatment, feel free to reach out to me! I’d be happy to connect.

Do Yogis Have Better Sex?

They must, right? I mean, with the kama sutra and tantric yoga, and countless articles in men and women’s magazines on “the best yoga positions to… [improve your sex life/ have a whole body orgasm/etc]”, how could they not? But if so, then why?

In the yogi world, connections between yoga and sexual health have long been presumed. Indeed, yoga has been proclaimed to be an ailment for almost every sexual dysfunction (e.g., low desire, sexual pain (vulvodynia), erectile dysfunction, premature ejacuation, anorgasmia). But shockingly, until now, there has actually been almost no scientific research testing the effects of yoga on sexual functioning! In fact, after hundreds of years of existence, to my knowledge, there has been only one controlled study with men with premature ejaculation, which has demonstrated yoga to be an effective treatment (Dhikav et al., 2007). There has also been some recent suggestion that yoga may improve lubrication in older women (“peri-“ and “post menopausal”) (Dhikav et al., 2010), and in women with metabolic syndrome (Kim et al., 2013). To translate, these are groups of women in whom impaired genital vasocongestion (i.e., blood flow) has been well documented, and so the increase in sexual function due to improved pelvic health from doing yoga is follows quite logically… (Interestingly, and in contrast to the sparse research examining the effects of yoga, the study of the application of mindfulness techniques – which are part of yoga - into sex therapy, has been much more established…)

So if there’s been little actual scientific research, then are all these claims about the sexual prowess of yogis just hearsay?

Not quite. Doing yoga probably isn’t going to make you a “superstar” in bed (whatever that means!), and it won’t guarantee multiple simultaneous orgasms, nor directly alter your libido (in fact, if what “hardcore” yogis or sadhus say is true, then in the renouncement of attachment, a certain form of desire might actually decrease). After all, brahmacharya (the controlling of all sexual energy) is one of the yamas (prescribed restraints) of the path of yoga. However, here is what a regular practice of yoga asana will do:

1. Yoga decreases stress and anxiety, and improves general well-being.

There is significant and compelling empirical work (from psychological and neuroendocrine studies) showing that yoga leads to meaningful reductions in stress, anger and anxiety levels (sympathetic nervous system activity), and to improvements in relaxation levels, contentedness and general well being, both in the short term (e.g. pre to post yoga class), and over the long term. With depression and anxiety being perhaps the leading psychological contributors to sexual dysfunction (by altering attention and impeding interest/ pleasure before and during sexual activity), any treatment that can address these symptoms is sure to create more space for sexual enjoyment. Put quite simply, providing that there is adequate sexual stimulation, sex is better when both your mind AND body are all in!

2. Yoga increases body awareness and decreases body objectification.

Although there are some that proclaim achieving a “yoga body” as one of the benefits of doing yoga (I like to think that every body doing yoga has a yoga body!), perhaps one of the greatest effects of doing yoga is in the enhanced levels of bodily (and genital) awareness and the non-bodily objectification that it promotes. Yogis are typically known to have greater interoceptive awareness, more attention and responsiveness to bodily sensations, and more comfort within their bodies – all of which are huge sexual aphrodisiacs! If you’re more comfortable, aware and responsive to what’s happening in your body, you’re likely to have more intense and pleasurable sexual experiences and the capacity for better sexual connections. You’re also more likely to know what does/ doesn’t feel good, what you want, and how you want it... There isn’t much that’s sexier than that.

3. Yoga fosters mindfulness.

Mindfulness refers to nonjudgmental, present-moment awareness, and is one of the main limbs of a yoga practice. Most of us are familiar with how mindfulness can be used to combat anxiety and depression, but even outside of the realm of mental health, the average person struggles to retain a curious, accepting, present-moment focus. We spend much of our time unknowingly jumping into the future (“I wonder if he’ll call me after this?” ), revisiting the past ( “I wonder what they meant when they said....?”), or analyzing our experience (“am I/is she enjoying this?”) - instead of just having the experience. Well, I’m sure you can imagine (or perhaps already know) the impact when we’re not present during sex – when we get lost in our stories, comparing the sex we’re having to the sex we’ve had before or that we think we should have, trying to control how we think the sexual dance should go (or what will happen after), or spectatoring on our own bodies, performance, or the performance of our partner…. We miss out on so much of the good stuff! The sexual dance comes to a halt. Pleasure is dampened. Sexual functioning deteriorates. In fact, distraction during sexual activity has been identified to be one of the major causes of sexual dysfunction for men (losing erections) and for women (losing desire). So perhaps not surprisingly then, a regular yoga (or mindfulness) practice, that strengthens the capacity to be present (and aware) with our actual embodied experiences is likely to lead to far hotter sex... literally and figuratively.

4. Yoga promotes pelvic health, strengthens mula bandha, and unblocks or moves stagnant sexual energy (kundalini).

Perhaps the most direct impact of yoga on sexuality is through its positive effects on pelvic health. Many yoga postures that involve perineal contraction (e.g., utkatasana (chair pose), mandukasana (frog pose)), have been said to tone and strengthen the pelvic floor muscles, increase genital blood flow, and build stamina and control over the pelvic musculature. If you’re someone with sexual pain (dyspareunia, vaginismus, etc), you might already be making connections here as to how and why this might help… If you’ve ever been to a yoga class, you may have received instructions such as “to contract your anus” or to “imagine you have to pee and need to hold it”. These bizarre instructions activate the mula bandha lock, which stretches the muscles of the pelvic floor, and balances, stimulates and rejuvenates the pelvic area through increasing blood circulation/ blood flow. How does this lead to better sex? Well, greater blood circulation translates to more genital blood flow (i.e., stronger erections, more lubrication), which can lead to greater pleasure and sexual interest, if your attention is directed to these enhanced sensations during sexual activity. In fact, activating mula bandha is the yogic equivalent to the famous kegel exercises women are often recommended to practice to aid in childbirth, to control and intensify orgasms, or to lessen the pain common to genital pain disorders like provoked vestibulodynia (PVD). For men, these very same exercises can build pelvic strength and control, which may lead to stronger/ more controlled erections and more powerful ejaculation.

Finally, for anyone interested in Tantra or Kundalini, these yogic practices (or the exercising of mula bandha) are also said to release blocked or stagnant energy in the root chakra (mooladhara) or second chakra (swadhisthana). The idea here is that this energy then rises up through the spine to the brain through nadis (energy channels that pass through the nerve centers or chakras), increasing sexual consciousness and thereby deepening pleasure. This means that previously blocked sensory messages from your genitals are now being positively received by certain parts of your brain, which will enhance desire and mental arousal “oooh, I like this, I want more of this”… This creates a feedback loop between the brain and the genitals with the brain then sending messages to increase physical arousal, which then leads to more intense feelings of being turned on. The scientific study of Kundalini and Tantra has only just begun and so the biomechanical secrets of pleasure in this energetic realm are only beginning to be unlocked...

5. It promotes trust, openness, and intimacy… especially when you bring your partner into your practice!

By now it may be clearer how practicing yoga might benefit your own sexual pleasure, (especially when you’re more relaxed, present, aware, and comfortable in your body), but what about your partner? For most people, sexual pleasure is enhanced by the sexual pleasure of our partners. So indirectly, through practicing yoga, your partner may experience higher levels of arousal by virtue of your own heightened pleasure, confidence, and sensitivity. In addition, the mindful embodied awareness that develops with a strong yoga practice fosters greater levels of responsiveness and connection between partners (providing your partner is also open), which typically facilitates more intimacy and trust (in being seen/ heard, held, and responded to), all of which are aphrodisiacs. Partnered yoga and mindfulness practices, such as synchronizing breath and/or movement can also lead to greater intimacy and trust, and ultimately to heightened mental and physical arousal. They may also foster more openness and a greater capacity to explore different positions and shapes (through increased flexibility, strength, and sensuality). Partnered practices, such as “acro yoga” or “therapeutic yoga” necessitate not only closeness and trust (within your own body and with the body of your partner), but also cultivate playfulness, fluidity and spontaneity. And with all of this to add to your sexual realm, just imagine where your sexual experiences could go...

So, in sum, while doing yoga might not directly alter your levels of desire/ arousal, it will likely enhance a lot of the factors that facilitate not just “good enough sex”, but the GREAT sex that most people long for…

Dhikav V et al. (2007) Yoga in premature ejaculation: a comparative trial with fluoxetine. J Sex Med 4: 1726–1732

Dhikav V et al. (2010) Yoga in Female Sexual Function. J Sex Med 7: 964-970

Kim H-N. et al., (2013). Effects of Yoga on Sexual Function in Women with Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Sex Med, 10:2741–2751.

The Dark Side of Mindfulness: What We Don't Talk About...

*Photo taken in Nepal by Sabina Sarin

I imagine you’re familiar with the term “mindfulness”? If you live in the west, and are over the age of 15, you’re likely aware that there has been a huge mindfulness movement, particularly over the past decade – a movement that some are satirically calling “McMindfulness”.

As a result of this movement, public awareness (and of course propaganda) about mindfulness has skyrocketed, and today, mindfulness is frequently proclaimed to be an effective treatment for countless issues, including depression, anxiety, eating disorders, sleep disorders, sexual disorders, chronic pain, stress, addiction, and trauma. In fact, some have even gone so far as to say that it is a “cure-all” for mental illness.

But I think that whenever anything is claimed to be a “cure all”, we need to be cautious. And we need to start asking questions. For example, what exactly is it curing? How is it curing it? When I practice mindfulness, is it the same as when you practice mindfulness? Are there any downsides to practicing mindfulness, or is it really the ‘holy grail’ of treatment? And if there are side effects, why aren’t people talking about them?

In actual fact, when we start digging into old case records, we find many reports of the negative side effects of mindfulness, mostly recorded in texts by Buddhist scholars, such as Master Chogyam Trungpa. Master Trungpa taught his students that meditation could in fact increase suffering, in part through falling into various “ego traps”. These ego traps include things like the identification trap (where we believe in some fixed person or entity that is enlightened – a.k.a., a guru), the permanency trap (the idea that we can hold onto some fixed truth), the centralizing trap (mistaking “nonattachment” for “detachment” or “withdrawal”), the accumulation trap (assuming there is some goal to meditation, when in fact there is nothing to add or take away, not even relaxation), and perhaps most importantly, the happiness trap or spiritual bypassing (believing that it is possible to be happy all the time if you just follow “the right steps” or do the “right” things). However, many of these findings have been ignored, particularly in the west, perhaps because the very foundation on which the practice of mindfulness meditation rests (i.e.., “no self” or ego dissolution) is the antithesis of everything that individualist cultures are structured around.

* Photo taken in Laos by Sabina Sarin

Which I suppose leads us to the question, what is mindfulness?

The definition has varied greatly, depending on which school of thought is defining it. One commonly accepted definition, offered by Jon Kabat Zinn, is that “mindfulness is moment to moment awareness, cultivated by purposely paying attention, in the present moment, as nonreactively and nonjudgmentally and open heartedly as possible.” However, Kabat Zinn later went on to confess that even this definition was too narrow and didn’t encompass all the concepts and practices of mindfulness. Most people, however, agree that mindfulness is a mental function that relates to attention, awareness, memory, and acceptance/ discernment.

But within the scientific and treatment realm, there is a lot of ambiguity about what kind of practice constitutes “mindfulness” and what sorts of explicit instruction people should be given. For example, can a traditional 10 day vipassana (incorporating 14+ hours of silence and body awareness meditation) with almost no instruction or guidance, be put in the same realm as spending 10 minutes on a cushion listening to a detailed guided meditation on modern apps like Headspace and Calm? Can the practices of breath awareness and open awareness be equated with the mindful eating of a raisin or mindfully taking out the garbage?

So far, there are no answers to these questions.

Research on the topic shows that mindfulness practices have only low to moderate effects in treating anxiety, depression and pain, and low effects for treating stress (this essentially means, that while the finding was statistically significant, it wasn’t particularly clinically or qualitatively meaningful). Although mindfulness has been associated with better emotional regulation and emotional intelligence, greater self compassion, better focus and presence, more thought detachment, and greater acceptance and well being, most of these findings have been reliant on self- report questionnaires. As you may imagine, self report is subject to numerous reporting biases, particularly social desirability effects – which, simply put, is when you know the answer that is expected/ wanted, and in order to please, you provide it.

Very few studies, however, have actually compared people in mindfulness conditions to other treatment conditions (the majority have compared effects for those not yet in treatment). Most studies have also varied in their definitions of the construct, the teaching method employed, the length of time of the meditation practice, the type of practice, and the variables that were measured in order to establish change. So in essence, a “mindfulness based intervention” (MBI) can mean many different things to many different people, which makes it hard to know what’s being assessed or how effective it is. Additionally, simply because an intervention is effective for some people doesn’t mean it’s effective for all people (there are often selection biases in study samples), and for some people, mindfulness practices might actually be harmful. In the words of Lazarus and Ellis, “one man’s meat is another man’s poison”. So it becomes really important to know for what and in whom MBIs should be used.

The problem is that few studies have actually measured or assessed adverse side effects. The majority have relied on people freely reporting side effects, which often doesn’t happen (because of social desirability effects). And this might be especially true amongst avid meditators, who are often drawn to the path because it is more “ethereal/ boundless”, and they are often seeking “enlightenment” or an escape from painful feelings - so they may not want to confess to certain negative effects (and instead, may be more likely “stay with it” in order to “be good”). In addition, some people might not report symptoms because a lot of the negative side effects actually seem to mimic what ‘mystics’ and spiritual texts have referred to as ‘steps on the path to enlightenment’ -- things such as seeing “the self” as an illusion (derealization), the dissolving of the ego (which might actually be the onset of a psychotic episode, and lead to disconnected schizoid states, instead of nonattachment), and blissful and altered states of consciousness (which might just be dissociation).

But rather than focus on the methodological shortcomings of the research, I would like to bring awareness to the potentially negative side effects of mindfulness practices, and to lay out some guidelines on how to use it safely, particularly in trauma survivors.

Confirmed findings, dating back to the 1960s, have illustrated the following possible side effects of meditation practices: increased anxiety, agitation, relaxation induced panic, tension/ constriction, depression, suicidality, disorientation, dissociation, thought disorders, derealization, depersonalization, psychosis, mania, grandiose delusions, identity breakdown, fragmentation, defenselessness, addiction, tremors, nausea, parapsychological perceptions, mobilization of the trauma response, and spiritual bypassing (the purification/ perfection of the human by “bypassing” unresolved wounds and painful feelings or developmental needs).

Interestingly, these effects are not dependant on the level of experience of the meditator – in fact, they are just as likely, if not more, to be found amongst more experienced meditators (than novices). According to David Shapiro’s work, 63% of experienced meditators had at least 1 negative side effect.

Now it should be noted, that not all of these challenges necessarily reflect psychopathology (disease) and some may in fact be necessary to the process, but I would like to draw attention to the particular impact they can have on those with unresolved wounds/ trauma. People with unresolved trauma typically lack the boundaries, containment, organization (in the nervous system), ego strength, affect (emotion) tolerance, and self regulation to pursue deeper practices. Part of the reason for this is that meditation makes you really aware of what’s happening in your body (and for some people, this may not be a good thing). It can also take you deeper into the recesses of your mind than you can deal with – revealing unprocessed and unconscious traumatic material.

Since trauma is stored in the body, not in the narrative or conscious mind, when this material resurfaces, it can go beyond the logical capacity to manage it. In other words, you suddenly become aware of ongoing bodily signals telling you that you aren’t safe, when in fact you are. So the practice can become physically intolerable – and can lead to physical pain, illness, and dissociation (to prevent feeling anything), at which point mindfulness is no longer accessible. Essentially, it is nearly impossible to “be present” and embodied, when you don’t feel safe.

Ironically, this might especially be true for the one group that mindfulness is commonly advocated for: people with high levels of anxiety and stress. Asking most people with severe anxiety to sit with their sensations simply isn’t possible because very often the sensations won’t just pass, but instead, they build, persist, and become unbearable, ultimately leading to panic, overwhelm, or complete collapse. Without the support of a trauma informed guide, who has knowledge of the brain and the nervous system (a rare occurrence in group based meditation settings, like vipassana), people can easily get re-traumatized or lost.

Also, practices like “no self” or “letting go” may be especially dangerous for trauma survivors because they can further the unhealthy belief that they aren’t allowed to have boundaries or a separate self, that their needs or emotions don’t matter, that they will be punished for unacceptable thoughts/ urges, or that they should feel shame for responses such as pleasing/ submitting, or conforming. In other words, you need to feel safe and have a solid sense of self before you can ‘let go’ and move beyond. You need to have control before you can let go of control – and letting go before you’re ready can be a major cause of psychopathology.

I think it’s fair to say at this point that we need a lot more research on mindfulness before we can begin using it as first line treatment. We also need to be careful about who we use it with. In general, a good rule of thumb is to avoid using these practices if you have any of the following: severe anxiety, clinical depression, unresolved or unintegrated trauma/ PTSD, psychosis/ schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe emotion dysregulation, or a severe personality disorder. It should also be avoided if you have poor ego strength or a fragile or rigid sense of self, poor boundaries, lack of empathy, rigid self control, severely insecure attachments, dissociative states, hypochondriasis and somaticization.

So you might be wondering, who should use it then? In short, it can be used safely in people with mild depression or past depression (as a relapse tool), mild stress, mild anxiety, and mild sleep or sexual difficulties. Essentially it is best used in people in reasonable health who are looking for a “wellness tool” that will help them become more present moment focussed.

And if you are going to engage in mindfulness practices to help you with a mental health issue, here are some important tips:

1) Keep your eyes open (especially if any of your wounds involved the ‘unseen’ or the inability to orient to the threat)

2) Use short durations for the sitting session, especially at first (5-10 minutes)

3) Make sure your space is well lit, scent-free, private, and that you know where your exits are

4) To calm the mind, focus on the breath, the temperature of the breath, or body sensations

5) Practice only in small groups

6) Feel free to practice in any position that feels comfortable and supports your window of tolerance

7) Make safety and stabilization a priority: begin with a grounding practice (focus on the feet, hands, rooting into the earth), orient to the environment (through sight/ sound/touch etc.), use walking/ movement/ eating meditations, guided imagery, and anything that will settle the nervous system

If you are practicing with the help of a guide:

1) They should use non-directive, invitational language – offering you choices (including opting out), inviting you to listen to your body and to be guided by your own experience, and refraining from telling you to “relax” or “let go”. It should be clear that you are the one in control of your practice, not your guide

2) They should allow you the opportunity to speak, and when they speak, it should be slow and in low tones

3) It is important that you feel supported and safe, that your physical and emotional boundaries are respected (e.g., regarding touch and physical distance) and that your guide is modelling self-compassion (although this can be overwhelming if you have never received this type of kind attention– go slow!)

4) Feel free to ask for information about the practice, about your body/ nervous system and about what you notice – knowledge is power!

5) It is okay to feel resistance or have self protective responses – they are there for a reason – honour them until you no longer need them

6) Make sure the guide is trauma informed and working within the scope of their training (tell them what you feel they need to know about you to make the space feel safer)

In short, a good rule of thumb is that if it doesn’t feel “right”, it probably isn’t. Trust yourself, and be mindful of the wisdom of your body. It knows best.