“YES, I EXPERIENCED [ BAD EVENT ] BUT IT WASN’T TRAUMA; I MEAN, IT WASN’T THAT BAD. OR AT LEAST, I WASN’T TRAUMATIZED… I JUST PUT IT BEHIND ME, DIDN’T THINK ABOUT IT, AND MOVED ON...”

*Photo taken by Sabina Sarin following a volcanic eruption and hurricane in Guatemala.

“I’M NOT TRAUMATIZED, I’M JUST [ANXIOUS/DEPRESSED/STRESSED/ ETC.]”

I cannot recall the number of times I have heard these sorts of statements from people that actually have quite significant, unresolved traumas... While no one wants to minimize a severe trauma (e.g. genocide) by placing it in the same category as a smaller scale stressor (e.g., a narcissistically abusive relationship), what I often see happening is that these smaller traumas go unacknowledged, and thus untreated. As a result, they often lead to instability in the nervous system (what we commonly think of as being “triggered”), manifest as physical or mental illness, or lead to future traumas. Typically, these manifestations are coping strategies, reaction patterns, or defences that mask the initial trauma or mitigate against feeling its effects. The untreated trauma not only puts the individual at risk for future illness, but also effects future generations. Trauma often gets passed forth within families and systems for many generations, leading to what is known as intergenerational or intesectional trauma. The purpose of this piece is to clarify some myths around trauma and to provide some of the trauma fundamentals that most people in this complex, and often chaotic, day and age should know.

What is trauma?

I think when most people think about trauma, they imagine the unimaginable: life or death situations that are terrifying and inescapable– war, genocide, torture, natural disasters, viral epidemics, bad accidents, etc. - what we call, “Big T Traumas”.

*Photo taken by Sabina Sarin in Poland

*Photo taken by Sabina Sarin

These kinds of trauma survivors typically go on to develop what we refer to as “PTSD” (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder), which involves frequent memories, nightmares and flashbacks of the event, avoidance of reminders of the event, emotional numbing/ detachment/ isolation, and chronic symptoms of physical arousal (increased heart rate, constriction, an exaggerated startle response, irritability or anger) (APA, 2013).

However, this is a somewhat incomplete definition of trauma and does not capture the range of experiences that can lead to a traumatic response. Nor does it represent the prevalence rates that we see for causes of PTSD, or the locus of the burden on the health care system. In actual fact, trauma is less about the event, and more about how one experiences the event. In other words, more crucial than whether one’s life is actually in danger is whether one BELIEVES that they are in danger and how much control (and support) they believe they have in coping with that danger. In other words, an event that results in someone feeling fundamentally unsafe, terrified, helpless and alone, has all of the ingredients for trauma. This can include anything from being followed at night on a deserted street, to being in an abusive relationship or growing up in a volatile (unsafe) or unstable home environment – what are known as “Little T traumas” . These events are not directly or intrinsically life threatening but may shatter a sense of safety or security, trigger other past traumas or wounds, produce traumatic charge in the body, and ultimately result in similar effects to other “Big T” traumas. According to the Center for Trauma and Embodiment, “trauma is something that is done to, forced upon, or taken away from someone, without their consent (or ability to consent) and beyond their control. “

At the same time, it should be noted that many people who experience life threatening situations (e.g., combat soldiers) often do not experience them directly as traumatic, and do not go onto develop PTSD. In fact, somewhat ironically, war veterans have some of the lowest rates of PTSD (Spence et al., 2011) amongst all groups of trauma survivors, perhaps due to the many protective factors inherent in their environment, including their greater levels of empowerment (choice/ control) and their built-in support system or “brotherhood”). In contrast, groups of trauma survivors that are more marginalized (e.g., LGBTQIA2S+, BIPOC, people with disabilities) are often over-/dis(em)powered, are typically alone in the experience of their trauma, and often more highly stigmatized and thus, less supported; consequently, they tend to be at greater risk for traumatic effects. And so given this, perhaps it is not so surprising that of all groups of trauma survivors, the highest rates of PTSD are found amongst victims of rape and child abuse (Spence et al., 2011). Right now, child abuse is considered to be the primary public health issue in both Canada and the US due to its pervasive impact on all aspects of mental/ physical health, and its cost on the health care system trumps almost any other illness (including cancer and heart disease) (van der Kolk, 2014).

Photo taken by Sabina Sarin in Vietnam

In fact, child abuse, or early attachment trauma (which includes fetal injury) is the single strongest predictor of whether someone will develop PTSD following an extreme stressor. Attachment trauma involves chronic experiences of feeling unsafe, hurt and helpless within an important caregiving relationship... (i.e., those that are supposed to love and take care of them). These children typically experience their homes as involving high levels of adversity, stress, chaos and/or low levels of support. They often develop what is known as Developmental Trauma, or Complex Trauma (CPTSD). On the other hand, children that grow up with a sense of safety, security, and nurturance with their caregivers tend to be more resilient following a potential life or death situation, and are more likely to bounce back afterwards. To eradicate child abuse would be to cut prevalence rates of depression by half, alcoholism by two thirds, and suicide/ homicide/ domestic violence by three quarters (van der Kolk, 2014).

In addition to developmental traumas, institutional or “systemic traumas” represent another form of trauma in which one is harmed by the very structure they rely or depend on to keep them safe (e.g., the police force, army, criminal justice system, or health care system.) These kinds of traumas are, unfortunately, highly common, and include things like racism, homophobia, patriarchy, poverty and discrimination on the basis of mental or physical disabilities. These forms of aggression or boundary violations (oppression by those with more power) exert their effect through invasion of the body/ mind/ spirit, and signal to the recipient that they are not being considered to have the same equality, integrity or dignity as someone else outside their “group”.

*Photo taken by Sabina Sarin in Guatemala

But also, people with these kinds of complex trauma normally go on to develop a number of other mental and physical illnesses including depression, anxiety, (auto)immune disorders, eating disorders, personality disorders, sexual disorders, autism and neurodiversity, as well as substance abuse disorders (often as defences against, or manifestations of the underlying trauma). This is why being carefully and thoroughly assessed by a trauma-informed psychologist (who have a specific toolbox of skills), and discussing the impact of some of these early childhood experiences can be really important. The effects of these kinds of experiences do not just “go away” by “moving on” or “rationalizing/ contextualizing” or “pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps.” Rather, they can lay dormant or masked for years and then show up as full blown illness. Conversely, very often, treating the underlying trauma is enough to eradicate the other symptoms (e.g., depression or substance abuse) altogether.

So you may be wondering at this point, why are the effects of trauma so devastating and far reaching?

What actually happens to the mind and body when there is a trauma?

I say the mind AND body, because despite popular thinking, trauma is not a mental disorder, its a physical one. Trauma is stored in the body, not the mind. Experiencing trauma changes the way the brain and nervous system develop in structure, or are wired (a form of neurodiversity), and so it logically affects every aspect of our lives (including our beliefs, feelings, and choices).

When faced with danger, our nervous system, and particularly the sympathetic nervous system (which includes the brain, spinal cord and various organs) becomes active, and hormones (such as cortisol) are released to help us take action, whether to fight, flee, freeze, or fawn. When we’re safe, the SNS deactivates, adrenaline (charge) is released, and the parasympathetic system (PNS) takes over so we can relax, regulate and integrate (rest & digest). In other words, on a more primitive level, we see the bear, we get scared, we run... when we know we’re safe, we shake it off, and relax.

What happens when there’s trauma is that the nervous system becomes overwhelmed by the event that it is trying to process and tolerate (because one feels/is unable to take the necessary action to combat the size of the stressor), so it gets stuck and the shift from SNS to PNS isn’t completed. As a result, the leftover electrical charge (from being in fight/ flight/ freeze mode) gets stored in the nervous system and often shows up in the form of various symptoms, such as emotion dysregulation. In other words, this stored stress response causes shifts from hypervigilance (alertness/ panic) to hypoarousal (collapse/ depression), and vice versa, which if untreated, start to affect every aspect of our lives (the byproduct of living under chronic stress).

Another way to look at this is that during a traumatic event, or when triggered, a split occurs between the rational mind and the rest of the mind/body – the rational mind shuts down or goes “offline” (and so we are no longer able to be relaxed, controlled, clear thinking, and grounded) and we consequently act from the more emotional, primal, parts of the brain (whose sole mission is to keep us alive).

But to understand this, you need to know a little about the brain.

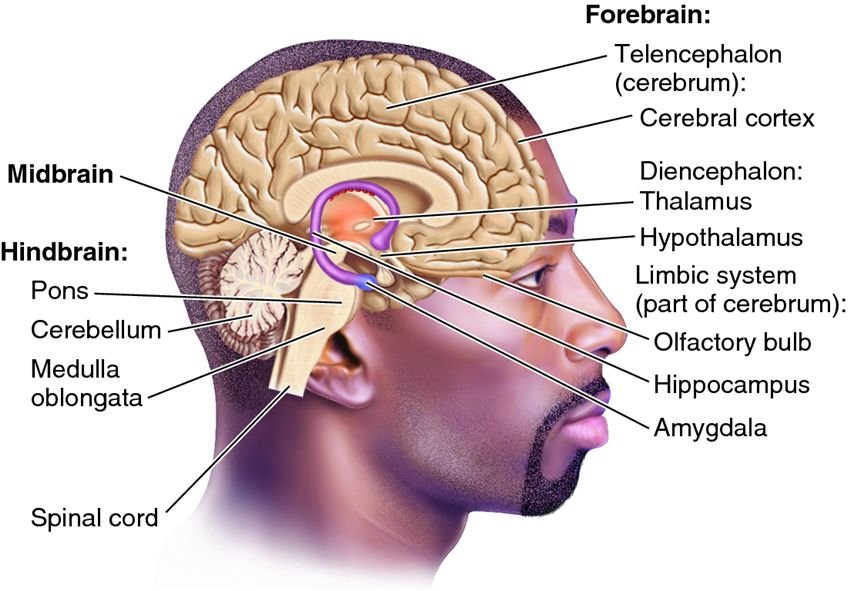

There are three main parts to what is called the Triune brain (Maclean, 1960):

1) Hindbrain – which is considered the reptilian part of the brain (or, “the lizard” as it is most primitive part and concerned only with survival. It includes the cerebellum, pons, and medulla oblongata.

2) The Midbrain, or Limbic System – which is considered the mammalian part of the brain (or, “the mouse”), which is common to all mammals and concerned with emotional security. It contains the thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, basal ganglia, and amygdala, all of which are strongly impacted by trauma. The emotional centers are highly active, processing impaired and memory fragmented.

3) The Neocortex or Prefrontal Cortex– which is new mammalian brain (or, “the monkey”), concerned with attachment and regulation processes, as well as rational thinking and emotion regulation. In trauma, it is less active and cannot override the activity of the other more emotional parts of the brain (which is why you can’t “think your way through a trauma response”.

But you may be asking yourself, what makes an event too much for the brain to process? Or how come some people get traumatized by an event when another doesn’t?

And this is where individual differences, such as early childhood experiences, come in. Individual differences emerge from everything that came before the event, and this includes past traumas, one’s physical and mental health at the time of the event, one’s capacity to process the event without becoming overwhelmed or stepping out of “ease” (the window of tolerance) , how much social/ community support they have to manage the event and its consequences, and one’s personal belief system regarding choice, capacity, and fear tolerance… all of which will ultimately determine the effects of the event(s) itself.

A closer look at this indicates that much of this concerns the size of your window of tolerance for stress. The window of tolerance is the intensity of stimulation that you can experience while still remaining calm, controlled and grounded. When we are outside our window of tolerance, it means that a situation has become “too much” for us, and we either become defensive (entering the Faux Window of Tolerance) dysregulated/ panicky, or shut down.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, we inherit our window of tolerance from our parents, and from how they responded to us when we were upset (a process called interregulation). Generally speaking, when we were upset, if they helped to soothe us and repair our emotions, we develop a large window of tolerance that allows us to have a sense of safety, trust, good relations with ourselves and others, and a capacity to tolerate and manage our emotions (self soothe).

If, however, our parents reacted in a way that caused us more distress, or that failed to adequately soothe us, then the brain develops differently (particularly the right side of the prefrontal cortex). This often leads to the development of an insecure attachment system, a more narrow window of tolerance, and consequently, more defensive coping (e.g., isolation, substance use).

In general, the wider the window of tolerance, the more intense arousal one can experience without becoming chaotic.

So, if you happen to have a more narrow window of tolerance, and then experience an event that is too much to process and the processing gets interrupted (e.g., you can’t run away, or you can’t fight back), that event is likely to lead to a traumatic response. Thus, one of the main goals of trauma informed therapy is to help clients “resource”, as a way of increasing the size of their window of tolerance, and building resilience.

Why can’t I remember details of my trauma?

It is possible to experience a traumatic event and not remember most of it, particularly if it occurred early in life, during one’s nonverbal stage of development. Sometimes people report just having a “feeling” that something bad happened, but having no actual memory (we hear this a lot with survivors of childhood sexual abuse).

And this is because not only is trauma stored in the body, but it is stored in the part of the brain that is nonverbal, visceral or experiential. And the part of the brain that sends information from the experiential part to the narrative intellectual part isn’t usually well developed in childhood, so traumatic experiences are often registered as “bad or yucky feelings”. In addition, the hippocampus, which is involved in memory formation and storage, is often impaired and/ or of a different structure in trauma survivors, leading to incomplete or fragmented memories.

But whether the mind remembers or not, the body remembers - “it keeps the score” (van der Kolk, 2014). And often all it takes is another experience that triggers a similar sensation in the body, to activate these old experiences, which ultimately allows the memory to resurface.

You may be wondering at this point, if trauma survivors have brains and bodies that are wired and structured differently, is full recovery or healing possible?

And the answer is YES (thank goodness for neuroplasticity!). But we have to go about it a bit differently than most other disorders.

Since trauma is stored in our body we need to heal it through the body.

And so “rational” therapies like CBT or psychoanalysis aren’t particularly effective, at least not at first when emotional management and embodiment is a struggle. You may know of people who talk something to death but it only seems to make it worse, or who have a clear understanding of their issues, but nothing changes. There are times when simply talking about or analyzing the problem “bypasses” the solution.

Instead, early in trauma healing, psychomotor therapies are the way to go, because these navigate around the rational brain and tap into the more primitive part of the brain where trauma is stored.

The idea behind any good trauma treatment is that it combines what is known about the brain and trauma, with the principles of mindfulness, breathing, resourcing, and healthy attachment

A person that is healed is one that feels safe, whole, integrated and accepted… and this happens largely through work that helps to release the built up electrical charge in the nervous system so that ease and gentle movements can start to happen again.

There are 3 stages that a trauma survivor will go through in the process of healing, and it’s important for your therapist to know what stage you’re in, because it tells them what needs to be done (Herman, 1997):

1) chaos – hyperarousal (chaos) to hypoarousal (disconnection)

In this stage, you may feel very dysregulated and fragmented (the word “broken” is used a lot by survivors to describe how they feel). The most important thing at this stage is to find a therapist you trust and feel safe with, that you can form a secure attachment with, that offers you choice and control and that has a strong understanding of trauma and its effects.

On your own, practices such as running, dance, gentle weight lifting, physical labour, restorative yoga, qi gong, and martial arts are wonderful adjuncts to help create some stability and to facilitate a release of built up stress. Paramount to this stage is ensuring that the trauma is over and feels over, which may include getting yourself into a new environment that feels SAFE. Support building (e.g., through support groups) is also essential.

2) containment – safety & stabilization

In this stage, you may feel more safe and it may feel like the traumatic event has actually come to an end. The work in this stage is to develop self soothing strategies, including grounding, emotion regulation, and orienting to the present. This stage is all about helping yourself become more resilient!

With your therapist, you should start to move into mindfulness work, relaxation work and resilience building.

On your own, yoga, mindfulness, dance, meditation and any practice that gives you pleasure (e.g., hiking in nature) is highly recommended.

3) coherence – integration

In this final stage, you may feel stronger, safer and more stable. This means you’re ready to start the process of safely letting go of control. This is the stage in which to revisit the memory of the trauma and its effects (but in diluted and titrated ways), and to complete the survival responses (e.g., fight/ flight/etc.) that once got thwarted. With your therapist, the trauma is processed in a slow and embodied way to facilitate the release of traumatic charge and to promote post traumatic growth and healing. Methods like EMDR, Somatic Experiencing, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, Cognitive Processing Therapy, Neurofeedback, Brainspotting, Internal Family Systems, and Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy can be excellent approaches at this time.

On your own time, its important to keep feeling, keep moving, and keep orienting to what feels “good”, after dipping into what feels “hard”.

Final tips on the healing journey: The DO’s

• Do keep your body moving, even in small ways; let it move how it wants to, even if it “looks” strange

• Do pay attention to your body and your limits, and set your boundaries

• Do read about trauma and express yourself through writing, creating, or by telling your support network how you feel and what you need

• Do orient to the present and the positive, feel your feet on the ground, find your centre, and feel your bodily container

• Do create a support network: support groups, positive environments, positive interactions; do find at least a few people with whom you feel safe and supported – trust your instincts

• Do take control and find ways to take your power back

The DO NOT’s:

• Don’t go too fast with anything – be patient and gentle with yourself

• Don’t spend too much time with the thoughts in your head – most of them likely aren’t true

• Don’t avoid or try to make it go away – but “do” choose “when” and “how much”

• Don’t blame yourself – it’s NOT YOUR FAULT, but healing is your responsibility. Try not to judge yourself …or your symptoms.

• Don’t isolate – but do not spend time with people that make you feel bad about yourself or your symptoms

• Don’t give up - Whatever happens, even in the hardest moments, do anything at all, even if it’s just to take a deep breath, and then another and then another after that... but do not give up. I promise you it will get better.

Healing is possible for anything and anyone.

IF this article has resonated or spoken to you in some way, and you’re interested in learning more, in being trained, or are interested in treatment, feel free to reach out to me! I’d be happy to connect.