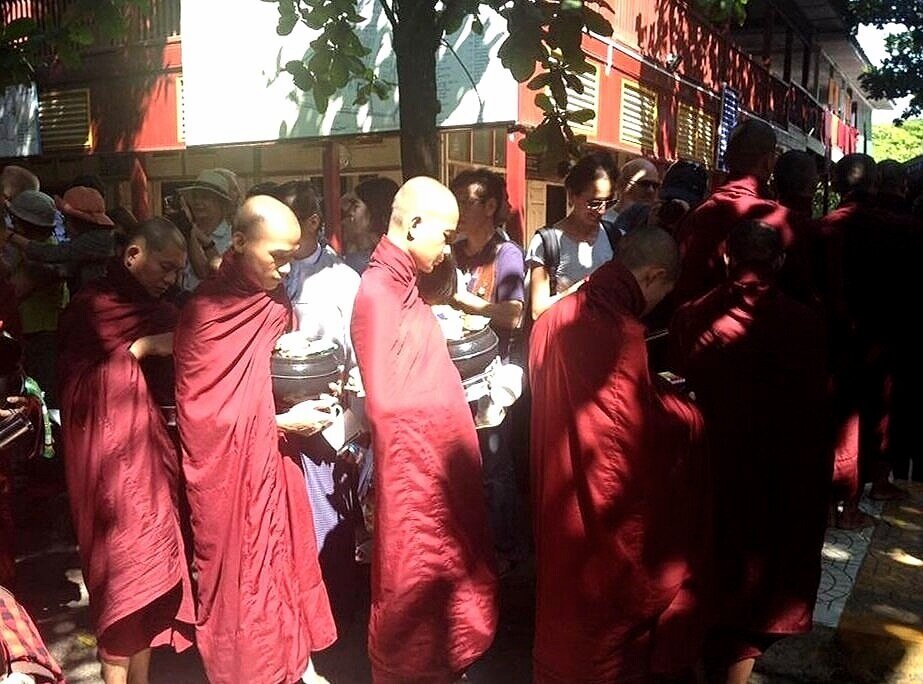

*Photo taken in Nepal by Sabina Sarin

I imagine you’re familiar with the term “mindfulness”? If you live in the west, and are over the age of 15, you’re likely aware that there has been a huge mindfulness movement, particularly over the past decade – a movement that some are satirically calling “McMindfulness”.

As a result of this movement, public awareness (and of course propaganda) about mindfulness has skyrocketed, and today, mindfulness is frequently proclaimed to be an effective treatment for countless issues, including depression, anxiety, eating disorders, sleep disorders, sexual disorders, chronic pain, stress, addiction, and trauma. In fact, some have even gone so far as to say that it is a “cure-all” for mental illness.

But I think that whenever anything is claimed to be a “cure all”, we need to be cautious. And we need to start asking questions. For example, what exactly is it curing? How is it curing it? When I practice mindfulness, is it the same as when you practice mindfulness? Are there any downsides to practicing mindfulness, or is it really the ‘holy grail’ of treatment? And if there are side effects, why aren’t people talking about them?

In actual fact, when we start digging into old case records, we find many reports of the negative side effects of mindfulness, mostly recorded in texts by Buddhist scholars, such as Master Chogyam Trungpa. Master Trungpa taught his students that meditation could in fact increase suffering, in part through falling into various “ego traps”. These ego traps include things like the identification trap (where we believe in some fixed person or entity that is enlightened – a.k.a., a guru), the permanency trap (the idea that we can hold onto some fixed truth), the centralizing trap (mistaking “nonattachment” for “detachment” or “withdrawal”), the accumulation trap (assuming there is some goal to meditation, when in fact there is nothing to add or take away, not even relaxation), and perhaps most importantly, the happiness trap or spiritual bypassing (believing that it is possible to be happy all the time if you just follow “the right steps” or do the “right” things). However, many of these findings have been ignored, particularly in the west, perhaps because the very foundation on which the practice of mindfulness meditation rests (i.e.., “no self” or ego dissolution) is the antithesis of everything that individualist cultures are structured around.

* Photo taken in Laos by Sabina Sarin

Which I suppose leads us to the question, what is mindfulness?

The definition has varied greatly, depending on which school of thought is defining it. One commonly accepted definition, offered by Jon Kabat Zinn, is that “mindfulness is moment to moment awareness, cultivated by purposely paying attention, in the present moment, as nonreactively and nonjudgmentally and open heartedly as possible.” However, Kabat Zinn later went on to confess that even this definition was too narrow and didn’t encompass all the concepts and practices of mindfulness. Most people, however, agree that mindfulness is a mental function that relates to attention, awareness, memory, and acceptance/ discernment.

But within the scientific and treatment realm, there is a lot of ambiguity about what kind of practice constitutes “mindfulness” and what sorts of explicit instruction people should be given. For example, can a traditional 10 day vipassana (incorporating 14+ hours of silence and body awareness meditation) with almost no instruction or guidance, be put in the same realm as spending 10 minutes on a cushion listening to a detailed guided meditation on modern apps like Headspace and Calm? Can the practices of breath awareness and open awareness be equated with the mindful eating of a raisin or mindfully taking out the garbage?

So far, there are no answers to these questions.

Research on the topic shows that mindfulness practices have only low to moderate effects in treating anxiety, depression and pain, and low effects for treating stress (this essentially means, that while the finding was statistically significant, it wasn’t particularly clinically or qualitatively meaningful). Although mindfulness has been associated with better emotional regulation and emotional intelligence, greater self compassion, better focus and presence, more thought detachment, and greater acceptance and well being, most of these findings have been reliant on self- report questionnaires. As you may imagine, self report is subject to numerous reporting biases, particularly social desirability effects – which, simply put, is when you know the answer that is expected/ wanted, and in order to please, you provide it.

Very few studies, however, have actually compared people in mindfulness conditions to other treatment conditions (the majority have compared effects for those not yet in treatment). Most studies have also varied in their definitions of the construct, the teaching method employed, the length of time of the meditation practice, the type of practice, and the variables that were measured in order to establish change. So in essence, a “mindfulness based intervention” (MBI) can mean many different things to many different people, which makes it hard to know what’s being assessed or how effective it is. Additionally, simply because an intervention is effective for some people doesn’t mean it’s effective for all people (there are often selection biases in study samples), and for some people, mindfulness practices might actually be harmful. In the words of Lazarus and Ellis, “one man’s meat is another man’s poison”. So it becomes really important to know for what and in whom MBIs should be used.

The problem is that few studies have actually measured or assessed adverse side effects. The majority have relied on people freely reporting side effects, which often doesn’t happen (because of social desirability effects). And this might be especially true amongst avid meditators, who are often drawn to the path because it is more “ethereal/ boundless”, and they are often seeking “enlightenment” or an escape from painful feelings - so they may not want to confess to certain negative effects (and instead, may be more likely “stay with it” in order to “be good”). In addition, some people might not report symptoms because a lot of the negative side effects actually seem to mimic what ‘mystics’ and spiritual texts have referred to as ‘steps on the path to enlightenment’ -- things such as seeing “the self” as an illusion (derealization), the dissolving of the ego (which might actually be the onset of a psychotic episode, and lead to disconnected schizoid states, instead of nonattachment), and blissful and altered states of consciousness (which might just be dissociation).

But rather than focus on the methodological shortcomings of the research, I would like to bring awareness to the potentially negative side effects of mindfulness practices, and to lay out some guidelines on how to use it safely, particularly in trauma survivors.

Confirmed findings, dating back to the 1960s, have illustrated the following possible side effects of meditation practices: increased anxiety, agitation, relaxation induced panic, tension/ constriction, depression, suicidality, disorientation, dissociation, thought disorders, derealization, depersonalization, psychosis, mania, grandiose delusions, identity breakdown, fragmentation, defenselessness, addiction, tremors, nausea, parapsychological perceptions, mobilization of the trauma response, and spiritual bypassing (the purification/ perfection of the human by “bypassing” unresolved wounds and painful feelings or developmental needs).

Interestingly, these effects are not dependant on the level of experience of the meditator – in fact, they are just as likely, if not more, to be found amongst more experienced meditators (than novices). According to David Shapiro’s work, 63% of experienced meditators had at least 1 negative side effect.

Now it should be noted, that not all of these challenges necessarily reflect psychopathology (disease) and some may in fact be necessary to the process, but I would like to draw attention to the particular impact they can have on those with unresolved wounds/ trauma. People with unresolved trauma typically lack the boundaries, containment, organization (in the nervous system), ego strength, affect (emotion) tolerance, and self regulation to pursue deeper practices. Part of the reason for this is that meditation makes you really aware of what’s happening in your body (and for some people, this may not be a good thing). It can also take you deeper into the recesses of your mind than you can deal with – revealing unprocessed and unconscious traumatic material.

Since trauma is stored in the body, not in the narrative or conscious mind, when this material resurfaces, it can go beyond the logical capacity to manage it. In other words, you suddenly become aware of ongoing bodily signals telling you that you aren’t safe, when in fact you are. So the practice can become physically intolerable – and can lead to physical pain, illness, and dissociation (to prevent feeling anything), at which point mindfulness is no longer accessible. Essentially, it is nearly impossible to “be present” and embodied, when you don’t feel safe.

Ironically, this might especially be true for the one group that mindfulness is commonly advocated for: people with high levels of anxiety and stress. Asking most people with severe anxiety to sit with their sensations simply isn’t possible because very often the sensations won’t just pass, but instead, they build, persist, and become unbearable, ultimately leading to panic, overwhelm, or complete collapse. Without the support of a trauma informed guide, who has knowledge of the brain and the nervous system (a rare occurrence in group based meditation settings, like vipassana), people can easily get re-traumatized or lost.

Also, practices like “no self” or “letting go” may be especially dangerous for trauma survivors because they can further the unhealthy belief that they aren’t allowed to have boundaries or a separate self, that their needs or emotions don’t matter, that they will be punished for unacceptable thoughts/ urges, or that they should feel shame for responses such as pleasing/ submitting, or conforming. In other words, you need to feel safe and have a solid sense of self before you can ‘let go’ and move beyond. You need to have control before you can let go of control – and letting go before you’re ready can be a major cause of psychopathology.

I think it’s fair to say at this point that we need a lot more research on mindfulness before we can begin using it as first line treatment. We also need to be careful about who we use it with. In general, a good rule of thumb is to avoid using these practices if you have any of the following: severe anxiety, clinical depression, unresolved or unintegrated trauma/ PTSD, psychosis/ schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe emotion dysregulation, or a severe personality disorder. It should also be avoided if you have poor ego strength or a fragile or rigid sense of self, poor boundaries, lack of empathy, rigid self control, severely insecure attachments, dissociative states, hypochondriasis and somaticization.

So you might be wondering, who should use it then? In short, it can be used safely in people with mild depression or past depression (as a relapse tool), mild stress, mild anxiety, and mild sleep or sexual difficulties. Essentially it is best used in people in reasonable health who are looking for a “wellness tool” that will help them become more present moment focussed.

And if you are going to engage in mindfulness practices to help you with a mental health issue, here are some important tips:

1) Keep your eyes open (especially if any of your wounds involved the ‘unseen’ or the inability to orient to the threat)

2) Use short durations for the sitting session, especially at first (5-10 minutes)

3) Make sure your space is well lit, scent-free, private, and that you know where your exits are

4) To calm the mind, focus on the breath, the temperature of the breath, or body sensations

5) Practice only in small groups

6) Feel free to practice in any position that feels comfortable and supports your window of tolerance

7) Make safety and stabilization a priority: begin with a grounding practice (focus on the feet, hands, rooting into the earth), orient to the environment (through sight/ sound/touch etc.), use walking/ movement/ eating meditations, guided imagery, and anything that will settle the nervous system

If you are practicing with the help of a guide:

1) They should use non-directive, invitational language – offering you choices (including opting out), inviting you to listen to your body and to be guided by your own experience, and refraining from telling you to “relax” or “let go”. It should be clear that you are the one in control of your practice, not your guide

2) They should allow you the opportunity to speak, and when they speak, it should be slow and in low tones

3) It is important that you feel supported and safe, that your physical and emotional boundaries are respected (e.g., regarding touch and physical distance) and that your guide is modelling self-compassion (although this can be overwhelming if you have never received this type of kind attention– go slow!)

4) Feel free to ask for information about the practice, about your body/ nervous system and about what you notice – knowledge is power!

5) It is okay to feel resistance or have self protective responses – they are there for a reason – honour them until you no longer need them

6) Make sure the guide is trauma informed and working within the scope of their training (tell them what you feel they need to know about you to make the space feel safer)

In short, a good rule of thumb is that if it doesn’t feel “right”, it probably isn’t. Trust yourself, and be mindful of the wisdom of your body. It knows best.